Introduction

“Comic strips have historically been full of ugly stereotypes, the hallmark of writers too lazy to honestly observe the world.” – Bill Watterson.

When reading old comic strips, it has to be understood that stereotypes will be encountered, regardless of the thoughts and opinions of the artist. The basic pro and con arguments go like this:

“The cartoonist is racist. Look at the way he draws African-Americans and Asian characters. The way they speak is also an embarrassment.”

“You have to place this work in a historical context. You are being politically correct to apply modern standards to the comics of the past.”

Were artists racists? Some probably were, but stereotypical depictions were probably more to do with lazy representations. An artist with no personal feelings might draw a character in a stereotypical way, just because that was the way others depicted them, and it was an easy visual shorthand. Stereotypes would also be used to depict good and evil characters (good characters would be more attractive than evil characters), social class (picture how a hobo might be depicted vs. a wealthy capitalist), and so on.

Is historical context just an excuse? Stereotypes were often included for comic relief, and were rarely central to the story, humor, or art. It is also important to remember the prevalent racism that existed at the time, especially in places like the American south. For example, depicting African-Americans positively would just as likely result in complaints from the reading public and newspaper owners which could affect the sales of comic strips. Over the decades, who was typically stereotyped changed. Any non-white, non-Protestant, non-English speaking people were fair game.

Can these still be enjoyed? There is a lot to love in early comic strips, so long as you understand the context. Being offended by certain depictions now shows how far we have come. However, it is understandable if it is just too much for some.

I will be showing examples below, so stop here if you don’t want to see them. These examples are ones I’m familiar with, there are many, many more.

African-Americans

The most common stereotypes depicted in comics were African-Americans (the largest minority in the USA), as many of the artists were Americans. These stereotypes existed since the beginning of comics, and date back to the days of minstrel shows. This easily depiction could even go so far as to depict Africans (in Africa) with American “black accents” and mannerisms. Since minstrel shows remained popular even in the 1920s and 1930s, it was normalized. Common characteristics included big lips, an ape-like appearance, speaking heavily accented English (also called “mushmouth”), and loud or shabby clothing. Men were depicted as lazy and would only have stereotypical jobs such as a porter, driver, race-track handler, or some other menial job. Women would either be maids or cooks. Many black maids are portrayed in the “Mammy” stereotype (fat, barely literate, and having no life outside the white family she serves). Actual Africans would be portrayed as savages, possibly with grass skirts or bones in their noses.

Examples: Smokey was a cook/valet/sparing partner for the title character in Joe Palooka.

Sunshine was Barney Google’s jockey and horse handler.

Opal was the maid in Boots and Her Buddies.

Rachel was the maid in Gasoline Alley.

An African in Mickey Mouse.

Other miscellaneous examples from Wash Tubbs, Moon Mullins, and Winnie Winkle.

Asians

Asians were another stereotyped group, but generally they were Chinese and Japanese. Asian characters were often portrayed as villains in the early 20th century (as a part of the “Yellow Peril”) as personified in the villain Fu Manchu. The common characteristics of Asians included poor English (Ls for Rs), slant eyes, and yellow skin. If the Chinese written language was presented, it would be a bunch of unintelligible scribbles since that is how they looked to the English speakers. An exception would be Hergé’s Tintin and the Blue Lotus since he actually had a Chinese friend who could help him with the characters (an example of actually knowing someone making a difference). Male characters would have buck teeth, bald heads, and pigtail “queues” (even though these were already out of fashion after the Chinese revolution of 1911). Chinese men would also have stereotypical jobs such as cooks and laundry men, though Japanese men were more stereotypically valets. Asian women were more likely to be portrayed as sexy, dangerous, and mysterious.

Examples: Connie (Terry and the Pirates) served as comedy relief. He was created specially for this role, where his mangled English often became the punchline. Since the strip takes place almost entirely in China or South-East Asia, there are all sorts of other characters who are more realistically portrayed. This generally can be applied as well to the Japanese who show up in the strip. Connie becomes a sympathetic character, though he does not lose his stereotypical appearance or speech.

The Dragon Lady (Terry and the Pirates) fits the mold of the sexy Asian, and her name became synonymous with women in that role. She also becomes a becomes a sympathetic character as time goes on.

Ming the Merciless from Flash Gordon is based on Fu Manchu and the concept of the dangerous Oriental trying to take over the world. Even his home planet is called Mongo, after the Mongols.

Other miscellaneous examples from Barney Google, Buck Rogers, and Detective Comics.

Native Americans

Native Americans (First Nations in Canada) were usually portrayed as “Injuns” in children’s comics, often as comic relief, or in adventure strips as villains. They were characterized as speaking poor English (sprinkled with “How!”, “Ugh!”, “paleface”, or “heap big”) and wearing buckskin, feathers, or other traditional dress that would not be common for the time. They were often lazy, thieving, or drunk. Even when stereotypical portrayals of other groups diminished in the 1950s, stereotypes of Native Americans continued much longer.

Examples: Lonesome Polecat from Lil Abner is one of those characters that continued right into the 1960s.

Many characters in Big Chief Wahoo were depicted in the stereotypical fashion, even though it was set in the present time.

Other miscellaneous examples from The Katzenjammer Kids, and Popeye.

When did it Change?

Changes began during and after the Second World War. Civil rights groups were able to make the argument that it didn’t make sense to fight Nazi racism in Europe while upholding segregation in America. The NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) were active in picketing and boycotting popular entertainment that depicted African-Americans in negative or stereotypical ways. Editors and artists became more sensitive to this, but rather than draw more realistic portrayals, offensive characters were written out of strips, and non-white characters became rare.

There were some exceptions to the stereotypes. For example, Rachel, the maid in Gasoline Alley, was a much more complicated character. Though her appearance was stereotypical, she was shown to have a life of her own, including friends, boyfriends, and family. These interactions would also become storylines, such as when she visited family in Alabama (where they treated her as a big city success), difficulties with boyfriends, or whether she should get married.

Her portrayal during the war years was praised in the African-American press. In 1944, “The character Rachel, who in the past has been a maid in the home of the Wallets, is a maid no longer. Last year she took a job in a defense plant. This year, with one of the characters home on furlough from the war, she is visited. A look at her home is enough to show you that something unusual in comic strips has taken place. Instead of the usual shanty in which Negroes are always supposed to live, she is housed in an attractive apartment house, with living room furniture that is quite as nice as that of her old employers.”

It should also be understood that there were African-American artists creating comics but they would not be as well known as they only appeared in African-American newspapers. A few outstanding examples include Bungleton Green (began in 1920) by Leslie Rogers, Sunny Boy Sam (began in 1928) by Wilbert Holloway, and Jackie Ormes who created Torchy Brown in 1937 about a nightclub singer moving from the South to Harlem. She also created Patty-Jo ‘n’ Ginger in 1945 that paired the wise-cracking and politically observant child Patty-Jo with her quiet but sexy big sister Ginger. Torchy would be revived in 1950 as Torchy in Heartbeats.

After the war, few comic strip artists would take the risk of including stereotypical characters (for fear of backlash from the community depicted) or include any non-white characters at all (for fear of backlash from bigots). A few might include a background character like Meena in Steve Canyon, (drawn realistically by Milton Caniff who based her on his friend and secretary, Willie Tuck), but she was still criticized for being a maid.

In 1961, Leonard Starr introduced a major African-American character in his strip On Stage, set in the theatre. The character of Philmore was patterned after Phil Moore, a well-known New York music coach and was a close personal friend of Starr. Four newspapers dropped his strip after the sequence with no reason given, but Starr knew why.

Cartoonist Morrie Turner created Wee Pals which debuted on February 15, 1965, it became the first American syndicated comic strip to have a cast of diverse characters. He had a difficult time selling the strip, since many editors were wary of “rocking the boat” with a strip showing black and white children playing together.

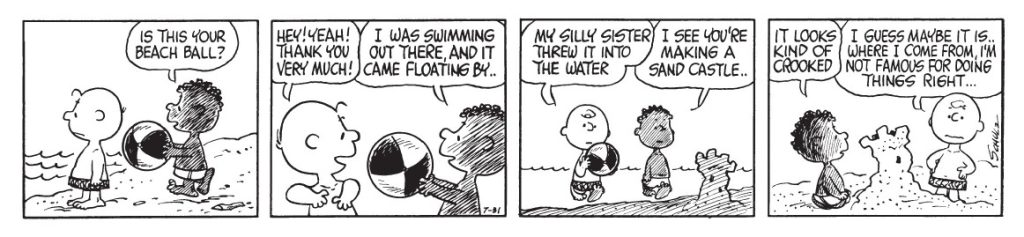

The largest and most popular strip, Peanuts, introduced Franklin on July 31, 1968. This was like a signal to other cartoonists. However it would still be slow going in the decades to come.

Sources

“What’s Not So Funny About the Funnies” by Ponchitta Pierce, November 1966 issue of Ebony magazine. https://books.google.ca/books?id=9zlc1lcRd44C&source=gbs_all_issues_r&cad=1

https://panelsandprose.com/2021/12/19/torchy-patty-jo-and-the-indispensable-jackie-ormes/

https://www.oerproject.com/blog/a-serious-history-of-black-comics-creators

https://inthesetimes.com/article/chicago-black-comics-culture-history

http://rcharvey.com/hindsight/tuck.html