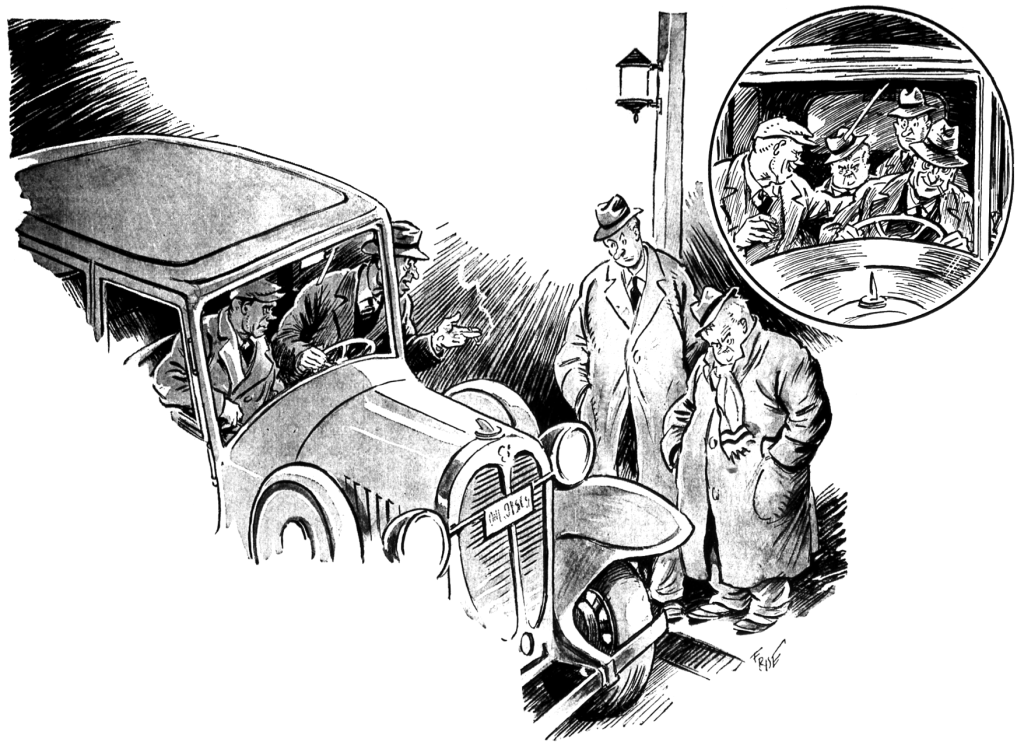

“I guess you gents know what you’re up against, huh? You know what end of a gun is loaded, ha ha!”

By Gregory Clark, Illustrated by James Frise, January 27, 1934.

“We,” said Jimmy Frise, “lead a pretty humdrum life.”

“You and me?” I asked.

“Yes,” said Jimmie. “Think of all the prize fighters, and the rich people that ride horses over high jumps, and the actors dancing in all the vaudeville theatres and everything.”

“Yes, but think,” I said, “of all the long rows of houses, miles and miles of rows of houses, and in them all the people sitting doing nothing, nothing is happening, nothing ever has happened, and nothing ever will happen!”

“But think of firemen,” said Jimmie, “never knowing what minute the fire bell will ring and they go lashing out into the icy streets, in dark and storm, to fight the demon fire. Think of Gordon Sinclair1 going to Darkest Africa. Of detectives, in the middle of the night, creeping along dark alleys, right here in Toronto, with guns in their hands, their teeth bared.”

“And think,” I said, “of all the people yawning in Toronto and lying back in their chairs, waiting for bed time, half asleep.”

“You have no romance in your soul,” said Jim. “Life should be an adventure.”

“In Toronto?” I asked.

“Yes, in Toronto. I bet you there is not a single street in Toronto, no matter how short,” said Jim, “in which, at this moment, tremendous adventure is not being enacted. Romance, tragedy, thrill, revenge, hate, yes, murder!”

“Not murder, Jim!” I cried. “Toronto won’t put up with murder. I grant you a little romance, yes. Romance of a decent sort. But revenge, murder, hate, all those things, no. Not at all.”

“You’re a typical Torontonian,” said Jim, caustically.

“I ought to be,” I said, proudly. “My great-grandfather was born here, in the village of York. I have remote ancestors buried under all the biggest skyscrapers in Toronto. There is not a downtown corner that one of my forebears did not own at one time or another and traded them to Jesse Ketchum2 for a hundred acres in Markham township.”

“You certainly show it,” said Jim. “In all my travels, from Lindsay to St. Thomas, I never knew anybody like the Torontonians for dodging life, though it be right under their noses.”

“We don’t dodge life, Jimmie,” I explained, “we just keep it calm and orderly.”

“You are only fooling yourselves,” said Jim. “Life and adventure are going on, right under your noses but you are too dumb to see it.”

“I defy you,” I said; “I defy you to show me any life going on in Toronto. I defy you!”

“Why,” cried Jimmie, “we could go and stand on any corner in Toronto, and unless you were too timid, adventure would come along and sweep you off in its embrace before you knew where you were!”

“Nothing of the sort,” I said. “A policeman would come along and order us to move on. That’s all that would happen.”

Challenging Adventure

“Would you like to try?” demanded Jimmie, his eyes narrow.

“It would be no use,” I said. “I know my Toronto.”

“Would you risk standing with me,” said Jim, levelly, “at any corner you like in Toronto and accepting the first adventure that comes along?”

“We would just feel silly,” I said. “Watching all the married couples out window-shopping after dinner.”

“You are as usual evading the question,” said Jim. “Will you come with me now, to-night, and stand on a corner and accept the first adventure that comes to us? Will you?”

“It is after 9 o’clock, Jim,” I said. “There will be only a few people walking along, coming from the first show at the movies.”

“I challenge you,” said Jim; “I challenge you to come right now and stand on any corner you like and see if adventure doesn’t come along and smack us on the nose!”

“It’s 9.20,” I said, “but I’ll come.”

So we got in Jim’s car that was out in front and we drove down along Bloor toward the city.

“There you are, Jimmie,” I said, waving at the familiar scene. “The only bright spots are the Italian fruit stores and, as you see, they are starting to carry the stuff indoors, preparatory to closing up. A few blonde ladies in lingerie shops standing looking sadly out their windows. Drug stores very busy selling cough remedies and soaps. Adventure, thank goodness, has been eliminated from Toronto the Good.”

“Name a corner,” said Jim, briefly.

“All right,” I said, “let’s just scramble it. Turn two blocks up, two blocks right, one block up and one block right, and where that will bring us out, I don’t know.”

“One corner is as good as another,” said Jim, turning up at a street I never saw before. We drove up two blocks, turned right and drove two blocks, then north another block and then right. Jim slowed down near the corner and parked. We got out. It was a typical west end corner. There were pleasant houses all around up and down the four streets at which we stood. Their lights burned dimly. Bridge lamps3 glowed softly in windows. Nobody moved. Not a living soul was to be seen. It was now twenty to 10 o’clock, and in all those pleasant, safe, comfortable homes there was not a sign or shadow of life. The Hydro lights glowed brightly.

“H’m,” I said, as we strolled to the corner and took up our stand.

“H’m is right,” said Jimmie. “Just look about you. Would you ever dream that in this quiet, peaceful neighborhood romances are being staged, tragedies and dramas being enacted? Can you hear screams, yells? Can you detect the odor of poisons, lethal gases, blood?”

“Jimmie,” I hushed him, “lower your voice!”

The calm was beautiful. For such a calm have we true Torontonians labored and voted and paid our taxes for a century.

“Know What You’re Up Against?”

We stood side by side. A car drove along the street. It turned carefully into a side drive. The gentleman driving it closed his garage doors. He stamped his feet carefully on the front walk to knock off any mud or snow that might be adhering to his feet. He coughed. He let himself into his house. All was quiet again.

“Well, well,” I said. “The great, wicked city!”

A boy on a bicycle rode past, singing softly to himself.

Two more cars drove carefully and pleasantly up the street.

“All I can hear,” I said, “is a faint radio, and if it isn’t Seth Parker4, it is one of his imitators.”

“Just wait,” said Jimmie, “this quiet is ominous, menacing.”

I smiled.

A car came slowly along to us. Two men were in it. As it came even with us, it braked and stopped.

The man at the wheel leaned out the window and said quietly:

“Are you the gents that were expecting us?”

My heart stopped beating.

“Yes,” said Jimmie.

“Hop in,” said the driver, reaching back and opening the rear door of the car. Jimmie took me by the elbow and shoved me into the car, ahead of him. He slid in beside me and slammed the door. The car started and the driver stepped on it. We lurched around the first corner and, gathering speed, raced southward.

“Easy,” I said nervously. “Not too fast.”

The second man in the car turned and rested his arm on the back of the front seat.

“We got to make it snappy,” he said.

“The Big Boy don’t like waiting around on a job like this.”

“No, of course,” said Jim, squeezing my knee.

“Was you waiting long?” asked the man facing us. I could feel him inspecting us with gleaming eyes as we flashed rapidly past lamp after lamp.

“No,” said Jim. “We hadn’t waited five minutes.”

“We wasn’t sure of the streets up in this swell neighborhood,” said the man. “Say, you gents don’t look much like what we expected to meet.”

“Is that so?” said Jim.

“No, we was looking for something…. well… a little more… how do you say it?”

“Sophisticated?” suggested Jim.

“Sure, that’s it,” said the man beside the driver. We were going faster than ever. We were headed out Queen St.

“Oh, I guess you can’t tell by the looks of a man what is inside of him,” said Jim.

“You sure can’t,” said he. “But still, I guess you gents know what you’re up against? Huh? You know what end of a gun is loaded. Ha, ha!”

“Ha, ha,” said Jimmie.

“Ha, ha,” said I. Jimmie squeezed my knee again.

Little Guys are the Big Shots

“The Big Guy.” continued the man in front, “he don’t want to deal with no pikers. He says to me, if these two guys can’t come across, then we’re going to deal with somebody acrost the line. See? Somebody that knows this sort of business. Regular guys, you understand?”

“Oh, sure,” said Jimmie.

“Have you had much experience along these lines?” asked the man in front, respectfully.

“Enough, I think,” said Jim, dryly.

“What I mean to say,” said he, “the thing you are going to do to-night isn’t done every day, is it? Not in Toronto.”

“No,” said Jim. “I guess it will give the old town quite a jolt.”

“It sure will,” said the man in front.

“You’ll have to keep mum,” warned Jimmie.

“I don’t want anybody going around shooting off his mouth, you understand.”

“No, sir: no, sir,” said the man in front. “The Big Boy has got me trained. I only wish I was big enough in your racket to swing a thing like this myself.”

“Why don’t you try some time?” asked Jimmie.

“Me?” cried the man. “Huh, I haven’t got the nerve. If I was all hopped up, and could keep myself hopped up for a year, I might take one swipe at it. But I know my limits, I leave jobs like this to the sharp shooters.”

“Excuse me,” I broke in.

But Jimmie grabbed my knee so sharply that all I could do was lean back in the seat and bite my tongue.

“Uh?” said the man in front. “What’s the little guy got to do?”

“Oh,” said Jimmie, “he’s the real performer to-night.”

But

“Excuse ME,” cried the man in front, jovially. “I beg your pardon, mister. I ought to of knew. All my life, I’ve noticed that it is the little guys that is the big shots. Leave it to a little guy to step in, do the trick and make a slick getaway.”

“I don’t shoot,” I stated, despite Jim’s sudden grab at the soft part of my leg above the knee.

“Haw, haw,” laughed the man in front, and even the driver laughed, though he should have been attending to his driving at the speed we were going. We were lacing in amongst some dirty old downtown back streets.

“Haw, haw, haw,” laughed the man in front. “Oh, no. You don’t shoot. Not if the Big Boy has picked you for this job. Listen, he never picked a muff in his life he’s worked with gents in your line of business all over North America.”

“In Chicago?” I asked.

“Yes, in Chicago,” said the man in front. “And that’s a tough town to work in, I’m telling you.”

“Ohhhhhh,” I said.

“I beg pardon?” asked the man.

“My friend was just yawning,” said Jimmie.

A Fit Place For a Murder

The car had slowed. We were picking our way down a narrow, half-lighted street. The back of warehouses, tall blind brick walls were massed about and above us, as the car jolted carefully in the narrow, ill-paved lane.

“Where are we?” I asked.

“We’re driving around to the back,” said the man in front. “The front doors are padlocked and under police guard. The Big Boy has the key to the back.”

“Police?” I asked.

“Sure,” said he. “The house is empty. isn’t it?”

“Ohhhhhhhh,” I said again.

“Uh?” said the man in front.

“My friend always gets sleepy when he he’s excited,” explained Jimmie.

“He ought to be excited,” said the man in front. The car had stopped in the shadowiest spot in all the long, narrow lane, and he was out and had opened the car door.

“Follow me,” he said quietly. “And hey, Andy, turn off them lights and wait ready to drive these gents wherever they say when the job’s over.”

He stepped up and unlocked the small door in the tall, ghostly brick wall.

“Jimmie,” I hissed, stepping tight against him, “this is gone far enough!”

“You’re going through with it,” replied Jim, in a murmur. “Get in there.”

The man was holding the door open for us, and we saw a narrow, dusty, unused corridor, dimly lighted by a dirty bulb hanging from the ceiling.

“Jim,” I said, “if I go another step, you’ll carry me!”

“Very well, I’ll carry you,” hissed Jim.

“Step along, gents,” said the man, whom I now saw to be a short, swarthy individual of foreign appearance.

Jim shoved me in, and the man slammed the door behind us.

“Watch your step,” said he.

He led us along the corridor, through dark chambers filled with the smell of dust and mould. It was a queer, unearthly place. A fit place for a murder.

We came out in a vast, empty chamber, filled with darkness. At a rough table on a platform sat a small man with a flashlight burning beside him.

“The Big Boy,” whispered our guide.

Jim took my arm and we walked across the creaking board floor, amidst that vast, echoing chamber, with its gaunt shadows cast by the tiny beam of the flashlight.

“Ah,” cried the Big Boy, leaping up. He was a tiny, weazened little foreigner, with his coat collar turned up and a wicked light in his close-set eyes. “So here you are!”

“Yes,” said Jimmie. “This is the man you want to deal with.”

The Big Boy reached excitedly and shook my hand.

“Are you prepared to do the job?” he cried.

“No,” I shouted, my voice echoing in the empty, forbidding and ghostly emptiness. “No, I am not!”

“You what!” gasped the Big Boy.

“My friend,” thrust in Jimmie, standing forward, “like all geniuses, is a little mad. That is his idea of a joke. Of course, he will do the job. Tell him what it is.”

“We’re Two Gunmen, See?”

“Listen,” said the Big Boy, swelling himself up, and staring hypnotically at me. “I picked you on your record. I heard about you all over America. I know what you can do. You’re the man I want.”

“No, I’m not,” I cried loudly. “You’ve got me wrong. I’m a law-abiding citizen of the city of Toronto. My forebears were archdeacons. Their portraits hang in Trinity College. I’m no gunman! Never!”

“Ha, ha,” laughed the Big Boy, like a rooster crowing. “That’s what I want exactly. A law-abiding citizen. The guy that runs this theatre for me has got to be law-abiding, or it would never get by.”

“Theatre?” I exclaimed.

“Sure, theatre,” said the Big Boy, puzzled. “What did you think it was, a bank?”

I gazed around at the fearful shadows.

“Aw, now, Mr. Perkins,” cried the Big Boy, “I know she looks terrible. But she’s been empty now three years. That’s why I got the lease so cheap, see?”

“Theatre?” I repeated. And Jimmie was standing closer to me.

“Sure,” said the Big Boy. “I want you should run this theatre for me. I got a swell lease. I pay you what you asked in your letter. I give you free hand. All I want is you should run it, and you know your way around Toronto.”

“I didn’t write you any letter,” I said. By now, I was getting a grip on myself.

“Listen,” said the Big Boy, shrinking inside his overcoat, “aren’t you Mr. Perkins? Hey, Sam, Andy! Come here. Who’s this you brought in here?”

The man who had sat in front of the car walked forward out of the shadows and stared at us.

“They was at the corner where he said to pick him up,” said the man.

“What is this?” yelled the Big Boy, shrilly. “A hold-up?”

“What was you doing at that corner? And getting in our car?” demanded the man called Sam, standing dangerously.

“Just a second,” hissed Jimmie. “We’re two gunmen, see? And we were waiting on that corner for an appointment with a job we have to do to-night. See?”

“Gunmen,” whispered the Big Boy and Sam, backing away.

“Yes,” said Jim. “And when this bird pulled up in a car we thought he was our party.”

“Oh, gosh,” breathed Sam. “Gunmen! In my car!”

“Excuse it,” said the Big Boy, hurriedly. “My boys will take you back. They’ll take you anywhere you say, gentlemen. Right away.”

“No, thanks,” said Jim. “We’ll have nobody driving us, thanks. Show us out.”

“Yes, sir; yes, sir,” said Sam, wobbling for the narrow corridor.

He let us out. Jim and I walked hastily down the lane. We got out to King St. and got in a King car headed west.

“Ah,” breathed Jimmie triumphantly. “So what!”

“Well,” I laughed, “so there was your adventure. A theatre lease!”

“Pardon me,” cried Jim. “We thought they were murderers, and they think we are gunmen. Isn’t that adventure enough for all of us?”

“But it is only thinking,” I exclaimed. “This is Toronto!”

“I know,” countered Jimmie. “But adventure and romance is mostly in our minds anyway.”

“I insist,” I said, “that adventure in Toronto is mostly misunderstanding.”

And it was after 11 o’clock when we got home.

Editor’s Notes:

- Gordon Sinclair was a popular international reporter for the Toronto Star at the time. Before World War 2, international reporting was still considered romantic and mysterious, especially outside of Europe and North America. ↩︎

- Jesse Ketchum was a political figure in Upper Canada in the early 19th century. ↩︎

- A bridge lamp is a floor lamp that has an adjustable arm and is used to light up the floor or a small side table. ↩︎

- Phillips Lord was an American radio program writer, creator, producer and narrator. He became a national radio personality after creating the character “Seth Parker”, a clergyman and backwoods philosopher, telling stories of rural New England life featuring ordinary folks singing hymns and telling jokes and stories. ↩︎

Leave a Reply