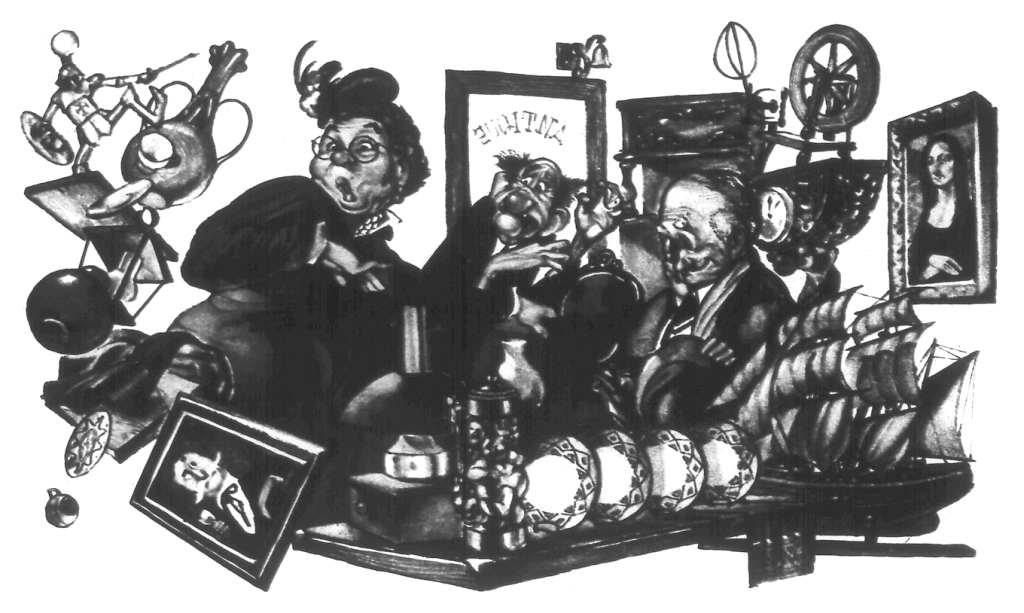

By Gregory Clark, Illustrated by Duncan Macpherson, January 28, 1950.

“This house,” gloated my Cousin Madge, “is a gold mine.”

She glanced both proudly and distastefully around her living room.

“See that damn thing up there?” She pointed to the mantelpiece.

On it stood a small glass dome inside which, stiff and stark, a bouquet of pallid wax and linen flowers bloomed funereally in pink and cream.

“Guess,” coughed Cousin Madge hilariously, “how much it is worth?”

“I suppose,” I reflected, “it might have great sentimental value…”

“Sentimental my eye!” wheezed Cousin Madge. “That thing is worth $20!1“

“Who to?” I checked.

“To anybody,” assured Madge. “I saw one exactly like it yesterday in an antique shop. Exactly.”

“Aw,” I protested. “Antique stores. You can’t go by the prices in antique stores. The antique dealers are up against a peculiar problem. They run stores. In stores, it is customary to put prices on things. So they just think of a number and put it on. The price of an article in an antique store, however, is merely a starting point. It indicates roughly the figure at which you are supposed to shoot. If they mark a thing like that glass dome full of wax flowers at $20, they expect you to say you would be willing to give $10. That being $8 more than they paid for it, they put on a doubtful air for a minute, and then reluctantly accept the $10.”

“You don’t like antique stores?” queried Cousin Madge, sharply.

“I love them,” I certified. “I haunt them. Antique shops, in this mass-production, consumer-conscious, price-fixed age, are one of the last refuges of individualism. The goods are individual. The seller is an individual. The customer is an individual, or he would be in a bargain basement, somewhere, instead of in a mortuary of bygone gewgaws.”

“But the prices, you said?” persisted Cousin Madge.

“Now, look!” I explained. “When you go into an antique store, you are looking for something unique. Something that cannot be bought anywhere else. Something that nobody else has got. Uncommon. Rare. And old. Facing you is a man or woman, the antique dealer, who, instead of getting a job selling mass-produced merchandise, has spent time and money, has travelled far and off the beaten track, going to a great deal of trouble to find and rescue these few, beautiful, odd things which, in this cold-blooded age, would normally have been thrown on the junk pile. Therefore, when you stand face to face with an antique dealer, two wholesome forces have met: your desire for something different and his satisfaction at having provided for your need.”

“Prices!” insisted Cousin Madge.

“No: there you go!” I protested. “You are trying to apply the principles of vulgar business to an art. The prices in an antique shop are dictated by the extent of your need or desire, in conflict with the gamble the dealer has taken in finding, buying and now offering to you this odd and curious item which, perhaps, you alone in all the world, want!”

Cousin Madge pondered this a moment, meanwhile continuing to gaze around her living room with that same expression of mingled affection and distaste.

“Twenty bucks!” she mused, as her eye again fell on that monstrosity of a glass dome with wax flowers.

“Where did you get it?” I asked.

“It was my mother’s,” said Cousin Madge. “It was given to her as a wedding present by her old Aunt Maria. That must be over 50 years ago, when every parlor had a glass dome on the mantel, either flowers, or stuffed birds or small white nude statues of slender ladies with their arms draped around each others’ shoulders, standing…”

“But why have you kept it?” I needled.

“Because I didn’t know what the heck else to do with it!” snorted Cousin Madge. “I just left it there, because where else could I put it?”

“It’s very quaint,” I confessed. “Very old fashioned very…”

“Ah, that’s not the ONLY treasure,” declared Cousin Madge, hitching herself powerfully forward in her chair. “Just take a look at that mantel. See those two china vases on the end? Pure Dresden. See all those knickknacks?”

She hoisted herself up and went to the mantel, and I followed her. On the shelf must have been 30 items: lustre trays, tiny bowls, leaf-shaped dishes. A bronze slipper with a maroon velvet pincushion cunningly concealed. A gilt-handled paper knife with a horn blade.

Wordless, Cousin Madge led me to a fancy walnut table in the corner. It too was covered with bric-a-brac, a hand-painted china tray, with plums and tulips, beautifully arranged so that you had to look twice to see which was which. Madge pulled out the table drawer: it was stuffed with bric-a-brac. She led me into the dining room, where a large old-fashioned china cabinet with glass door stood back, in the gloom.

It was full of china of every period and style, as well as cut glass vases, carafes, olive trays, pickle dishes. She took them out and clinked them with her finger nail. Real stuff, see?

And silver. Silver entree dishes, silver candlesticks, silver pie servers, pickle forks, sugar tongs, salt cellars, salt bowls, all tarnished from, long disuse.

“This house,” asserted Cousin Madge loudly, “is a gold mine.”

“You should give a lot of this stuff away,” I reproved, “to your nephews and nieces.”

“The heck with them!” said Cousin Madge, heartily. “I’ve got a better idea. I’m going to make myself a little dough.”

“Are you going to try to sell some of this?”

“I got the inspiration yesterday,” announced Madge, “in that antique store. I just happened to drop in, to get a closer look at that glass dome and wax flowers. You could have knocked me over when I asked the prices! They’re terrific.”

“Sure,” I corrected, “but the value of these things of yours, tucked away in drawers, has nothing to do with the price of goods sitting for sale in an antique shop. They may sit there for months, years.”

“According to his figures,” asserted Madge, “I bet I’ve got $200 worth of junk, right here. And I’d never miss the stuff.”

“You wouldn’t get $50 for it,” I ventured.

“I bet I’d get $100,” cried Cousin Madge. “Maybe more!”

“Did you discuss the matter with the antique shop man?”

“How could I,” said Madge, “when I was asking the price of everything? I didn’t want him to think I was checking on him.”

“He probably suspected,” I offered.

“Have you got your car outside?” asked Cousin Madge.

“I’m on my way downtown, an important interview,” I hastened.

But I am always too late.

“Put the kettle on and get a cup of tea ready,” commanded Cousin Madge. “I’ll be dressed in a jiffy.”

In a few minutes, she came back downstairs carrying an empty suitcase and a large wicker market basket. From the kitchen cup- board she gathered up a bunch of old newspapers.

Then, calmly and with the decision that indicated she had given the matter all the thought it required, she proceeded to loot her home.

First of all, down off the mantel came the family heirloom, the glass dome with wax flowers. This she tenderly packed with clumps of newspaper in the big wicker market basket. Off the mantel also came lustre trays, the bronze slipper, the knife, a bulbous glass paper weight showing a picture of the Crystal Palace, the two Dresden vases. The mantel looked horribly barren when she had stripped it. But the market basket was bulging.

From tables and shelves, from the china cabinet and from the cupboard ends of the dining room sideboard, she took silver dishes, bowls, forks, servers, tongs; cut glass dishes and bowls of all sizes; china objects of every sort and description. She worked in about 12 assorted cups and saucers.

“Indian Tree,” she related, as she packed them. “Royal Doulton. Bridge prizes. Christmas presents. For years and years…”

I helped carry the loot out to my car and we set the basket and suitcase, together with an overflow carton, in the trunk of the car. Cousin Madge directed me to the street where the antique shop of her choice was located.

The instant we staggered through the door with the suitcase and basket, I knew Cousin Madge was recognized.

The antique man tightened his lips, scratched his head and rolled his eyes up to the ceiling all in one fluid gesture.

“I thought,” announced Cousin Madge, heartily, “that you might care to look over some stuff I have here. This is just a sort of overflow, that I am prepared to sacrifice, of course, provided I get a decent price.”

“Lady,” said the antique man, “look! Have I any more room for anything? Can you see ONE SPOT where I could lay anything down?”

“The things I have here,” said Cousin Madge, moving cautiously toward him between the small laden tables, the shelves, the counters, “is away ahead of anything you’ve got here.”

“No doubt, lady, no doubt,” said the antique man, who spoke with a heavy Glasgow accent. “But it so happens I am overloaded. Upstairs, in five rooms. I’ve got tons of stuff. Some of it I haven’t even unpacked in two or three years.”

“I’d like you to see this,” soothed Cousin Madge, in her best dominating style. “One look and you’ll want it.”

“Pardon me,” said the Scotsman, scratching his head with both hands, as Cousin Madge opened the suit case. “But up country, I’ve got a barrel of stuff in this town, a box of stuff in that town, that I simply haven’t got room for here.”

Cousin Madge spread the suitcase on the floor and scrunched down to unpack it. She cast the rumpled newspaper wads aside, and one by one placed the objets d’art on an antique oak bench that was handy.

Cut glass dishes, silver pickle forks with pearl handles, Indian Tree cups and saucers.

“Tch! Tch! Tch!” said the antique man.

“Now, just a minute,” whuffed Cousin Madge, signalling me to fetch forward the wicker basket.

From the market basket, flinging the balls of newspaper aside, she triumphantly drew forth the glass globe and the wax flowers; the bronze slipper; the Dresden vases.

The antique man groaned faintly.

Cousin Madge took a long breath and straightened up from her squatting position.

“Lady,” said the antique man, “I’m afraid you didn’t hear me. I tell you I have five rooms upstairs packed solid full of this stuff. Up country, in this town and in that town, I have stored barrels and packing cases…”

“This is far ahead of what you’ve got on display here,” said Cousin Madge firmly.

“Okay! Look:” said the antique dealer. “I’ll: give you $10 for the lot!”

It was his way of getting rid of her, I suppose.

But Cousin Madge looked at him with a sudden empurpling of the face and a swelling of the body.

She struggled to repeat the words, $10.

In her effort to do so, Cousin Madge took a step backward. Now Cousin Madge carries behind her a promontory of which she seems to be unaware.

As she stepped back, there was a sudden slither and a loud crash.

She had upset a table laden with treasure.

“It’s always the way,” moaned the antique dealer, as the three of us scrambled around picking up the pieces. “It’s always the ones trying to sell who smash the stuff!”

Quite a lot was broken. The spindly table on which the objets d’art had stood was broken. The lid of a small china box was smashed. A fragile glass vase, “priceless, priceless!” the dealer said, was in fragments.

The antique dealer decided, when we were all tidied up and relaxed, that he would make an inventory and let us know what we owed him. He would keep the stuff we had brought in as security.

But when I suggested that a friend of mine, an insurance adjuster, who knew a good deal about antiques, would call and help him make the inventory, the antique dealer agreed to take, at once, in payment of the damage, two cut glass pickle dishes, one pearl handled pickle fork, both Dresden vases and the glass dome with wax flowers.

When Madge and I got home with the balance of the treasures, and were seated safe and sound with a teapot, she said:

“Well, I’m glad to be rid of that glass dome and those dismal bloody flowers!”

Editor’s Note:

- $20 in 1950 would be $256 in 2025. ↩︎

Leave a Reply